|

|

| introduction | yap | pohnpei | chuuk | palau | marshalls | ||

|

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN MARSHALLS

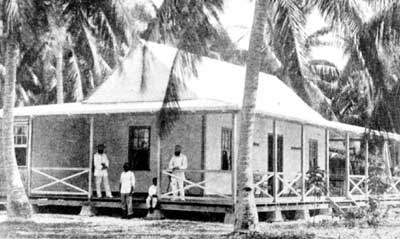

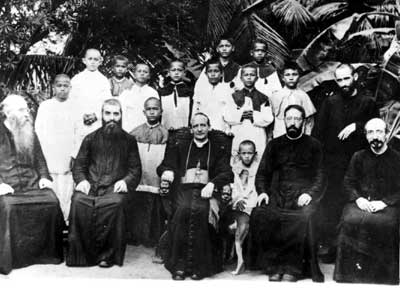

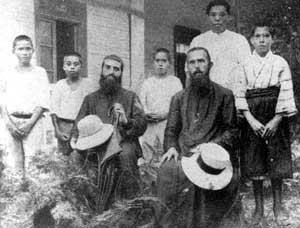

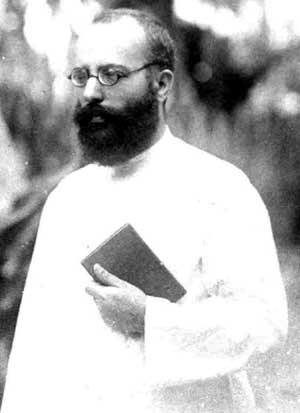

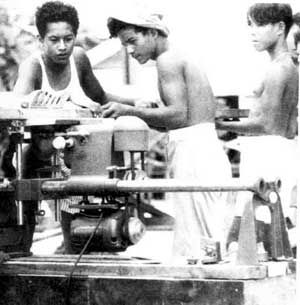

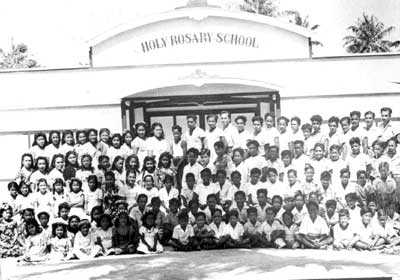

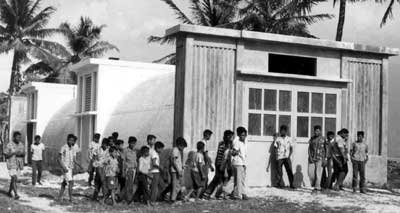

Breaking the Ground In late October 1891, Fr. Edouard Bontemps and Br. Conrad Weber landed in Jaluit with a few Gilbertese catechists to begin Catholic missionary work in the Marshalls. Fr. Bontemps and Br. Weber, members of the Congregation of Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, lost no time in getting down to work. They acquired a small plot of land with a few simple houses from a trader who was leaving the island, and within a few days they set up a chapel and prepared a building to serve as the school they intended to open. Then, as their preparations were nearing completion, Commissioner Brandeis, the head of the German government in the Marshalls and himself a Catholic, informed the missionaries that they would have to suspend all religious activities until he received formal approval of the new mission from Berlin. The Marshalls had been christianized since 1857 by American Congregationalists and was by that time thoroughly Protestant. German authorities feared that the news that Catholics were entering their field would provoke a strong reaction, perhaps even an uprising. The government was well aware of the open hostility that periodically flared into violence in the Protestant Gilberts ever since Catholic missionaries had landed there three years before, and it wanted to forestall similar problems in the Marshalls. Disappointed that he could accomplish so little under the circumstances, Fr. Bontemps left Jaluit with his small band just two weeks after their arrival. For years Micronesia had been a shadow vicariate, established by decree in 1844 but neglected in favor of missionary work in other parts of Oceania. An ancient Marshallese chant recounts the massacre of eight men, thought to be Catholic missionaries, who washed up on Arno in the early 1840s. This ill-fated missionary party may have been a portion of the French missionary expedition headed by Fr. Etienne Rouchouse that set out for Hawaii in 1842 but was never heard of again. At any rate, this tragic incident was the outcome of an accidental encounter, and Catholics made no further attempts to reach the Marshalls. Then, in 1881, Rome asked the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, a congregation founded in 1854 by a French priest, to begin evangelization in Micronesia. The task became manageable after the Carolines was entrusted to the Spanish Capuchins in 1886 and became a mission of its own. In 1887, the Sacred Heart Missionaries sent their first priests, all of them French, to the Gilberts,  Fr. Joseph Bontemps, MSC "and waited for the opportunity and personnel to expand their work into the Marshalls. German authorities in the Marshalls, although nervous about possible religious conflict, were delighted at the Catholic initiative. A few years after the two missionaries showed up in Jaluit, government officials made a formal request of Rome for Catholic missionaries to the Marshalls. The government wanted German-speaking missionaries in the Marshalls because of the beneficial cultural influence they could have on the people. Catholics were preferred to Protestant because the government's past relations with the Congregational Church in the area had been so troubled. The Sacred Heart Missionaries did not yet have the personnel to staff a new mission, but they promised to do so at the first opportunity. In the meantime, they would explore the field that they were making plans to evangelize.  Br. Conrad Weber, MSC In 1896, five years after his initial visit, Fr. Bontemps made another trip to Jaluit, again with Br. Conrad Weber. The priest returned to the Gilberts after a short stay, during which he baptized one or two half-caste children, but Br. Conrad remained on Jaluit for six months improving the property and teaching school to whatever students might turn up. Meanwhile, the Commissioner of the Marshalls made a visit to the newly founded German headquarters of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart in Hiltrup to press for the establishment of a permanent mission in the Marshalls. By 1898 negotiations between the government and the superior of the congregation were drawing to a conclusion. The Marshalls, together with Nauru, were to be assigned to the German province, while the French Sacred Heart Missionaries would retain the Gilberts. At last, in January 1899, Catholic missionaries came to stay. Louis Coupp , the Bishop of New Britain, brought Br. Calixtus Bader to Jaluit and installed him as temporary overseer of the mission. Although the bishop himself spent only two months on Jaluit, Br. Calixtus was more than equal to the task of organizing what was to become the main station in the Marshalls. On land bought from the Jaluit Company, he single-handedly built a new residence, renovated the small chapel, and in March opened a school for the seven students stalwart enough to brave the opposition of local pastors. After a year of ground-breaking work, Br. Calixtus was joined by Fr. Jacob Schmitz, the first priest permanently assigned to the Marshalls. An additional two priests Frs. August Erdland and Friedrich Gr ndl and two brothers Brs. August M ller and Heinrich Egbers were sent to the Marshalls in 1901. The following year saw the arrival of the first sisters, five religious of the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, a congregation founded by the MSC priest Hubert Linckens to assist his own order in its overseas work. Landing in Jaluit in October 1902, Srs. Johanna, Stanisla, Magdalena, Aloysia and Hubertine immediately took up work in the girls school there. All these new personnel staffed the Jaluit mission station, a five acre piece of land that fronted the ocean side of the island. The small church built of thatch was flanked on one side by a building that served as the convent and the girls school, and on the other by the rectory and the boys boarding school. The convent and the rectory were spacious wooden buildings with shaded verandas, after the European fashion of the day. Since the Marshallese population was solidly Protestant and the number of Catholics among the foreign population was so small, the missionaries could do very little direct pastoral work. The heart of their mission program on Jaluit was the schools there were separate schools for boys and girls, all of whom lived with the priests and sisters as boarders. In 1903 there was an exclusive clientele of 32 boys and 25 girls: most of them the children of foreigners or half-castes, and a few the offspring of high chiefs. Not all the students were Catholic in fact, the majority were not but their parents gladly entrusted them to the Catholics because of the superior education they offered. The missionaries modelled their educational program on the German public elementary school. They offered eight grades of instruction. Classes were held from 8 AM until noon and again in the late afternoon, with all teaching done in German. The children were taught to speak, read and write German, in addition to arithmetic, geography, penmanship, religion, and the usual elementary school fare. For the rest of the day, students worked with their mentors around the mission premises. The boys did simple carpentry and household chores, while the girls learned to cook and sew and keep house in the European mode. This contrasted sharply with the Protestant-run local schools, conducted in Marshallese and aimed chiefly at teaching the young how to read the bible.  The first rectory on Jaluit "The sisters fed their charges rice and meat or raw fish for the main meal and home-made bread and tea in the evenings. When the number of girls grew and their quarters became too cramped, a new and larger convent was built. This new building was located on the shore of the mission compound, but closer to the rectory so that the sisters could cook for the priests and brothers as well as for themselves. The school children were under close supervision. Br. Heinrich, a big-boned man with a hearty laugh who served at the school for years, awakened his boys each morning with a single clap of his hands and led them in their evening prayers before they retired for the night. Years later he was remembered by his former students with affection that bordered on reverence. Running a boarding school was an around-the-clock job, but the missionaries were more than willing to put up with the demands, for they felt that only by removing the children from the sometimes appalling conditions of their own homes and situating them in a religious milieu could they provide a strong enough foundation in the faith to see them through the rest of their lives. Indeed, some results from the school on Jaluit soon began to be seen. On Christmas 1902, a few months after the opening of the girls school, the first pupils were baptized: five boys and three girls. That same year a visiting priest en route to another mission was greeted at the dock by a group of school children who welcomed him in his own language and carried on a lengthy conversation with him in German. Later in the day the children sang the high mass for the feast of the Assumption while young outsiders watched the spectacle with their noses pressed against the chapel windows. Other visitors in later years were equally impressed with the recitations of German poetry and dramatic presentations by the students, not to mention their ordinary conversational ability in German. The Jaluit mission school was winning admiration throughout the Marshalls and in even wider circles; it quickly established a reputation as the premiere school in all of Micronesia. Catholic mission work soon was extended from Jaluit to other islands. In 1902 a mission station was opened on Likiep under Fr. Leo Kiefer and a brother. When Fr. Kiefer died suddenly less than a year later, he was succeeded by Fr. Johann Wendler, who was pastor on the island until his own death in 1912. The first three sisters arrived in January 1906 to work in the girls school, which had only 12 students. The handful of boys were taught by the single MSC brother. The schools on Likiep, unlike the Jaluit schools, initially had no boarding facilities whatsoever; the entire student body, which soon grew to 35, were day students. The mission work on Likiep was far less centered on the school than it was on Jaluit. A number of people on Likiep, especially from the DeBrum family, were baptized, and a sub-station was soon opened on Utirik and serviced by the Maria, a small single-masted, ocean-going boat that was built by Br. Neumann and two Marshallese craftsmen. As the Catholic population from the area  Mission residence on Likiep increased, boarding students were accepted from the other islands, and by 1911 there were 15 boys and girls living with the missionaries on Likiep. Nauru, a part of the Marshalls Mission, was the next destination of the MSC missionaries. In early 1903, Fr. Gr ndl and Br. Calixtus were transferred from Jaluit to staff this new field, with sisters following them a year later. Within the next few years two separate stations were in operation on the island: Arubo and Menen. Although staffed by only two priests and a few sisters for the next several years, conversions to Catholicism were far more numerous than in the Marshalls. Meanwhile, the flow of new personnel into the mission continued. Another two priests and two brothers arrived in 1904, another pair in 1905, and six more men the year after. Between 1904 and 1907, three groups of missionary sisters arrived in Jaluit to add another 11 religious to the mission rolls. To assist them in gaining fluency in the language, the new missionaries had a dictionary and grammar of Marshallese that was written by Fr. August Erdland in 1903. This work was subsequently published, as were numerous other articles on the language and culture penned by Erdland. The mission was rapidly growing in size and stature, and soon it was separated from Melanesia to form its own ecclesiastical jurisdiction. By a decree of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith on September 12, 1905, the Marshall Islands was made a separate vicariate and Fr. August Erdland was appointed the apostolic vicar. When word of the ecclesiastical change in status reached Jaluit, the island was still recovering from a devastating typhoon that took it by surprise on the Feast of the Sacred Heart, June 30, 1905. As the surf was building up early in the storm, an enormous wave battered the convent  Priests in the Marshalls Mission, 1910 "crumbling three of its walls and sending the sisters tumbling on a stream of water towards the center of the island. One of them was floating unconscious when she was fished out of the sea. The storm worsened during the evening and the sisters, who had never been through this experience before, said their final goodbyes to one another and waited to be swept away to their death. They survived, but most of the mission property did not. The rectory was the only building left standing, and even that had sustained serious damage. The island was a dismal sight; nearly everything was in ruins. Mission losses alone amounted to 60,000 German marks, or $15,000. For the next few months, until a temporary convent could be erected, the sisters and their 31 boarding students lived in an undamaged part of the rectory, while the priests and their students found shelter elsewhere. It was not until May 1906 that the repairs on the former convent were completed and the sisters could return to their own building.  Sisters and boarding students on Likiep The mission reached the furthest extent of its expansion when a last station was set up on Arno in 1906. Fr. Joseph Filbry was sent with a brother to open the station in Ine, and two years later Srs. Margareta, Bonifazia, and Severine were assigned to help in the girls school. The mission complex was little different from any other during that period: the church was a simple thatched building, and the rectory and convent were substantial wooden buildings large enough to hold a number of boarding students. At first the people of Arno seemed surprisingly receptive to the Catholic school; 30 girls were enrolled during the first few months. Then, as local opposition mounted, students started withdrawing from the school. In time the sisters had to struggle to retain even three or four of their most loyal pupils, and finally there was but a single girl left in the school. Things improved afterwards the enrollment built up once again and the sisters made a few conversions but Arno remained the most difficult and unrewarding of the mission stations. To provide a link between these distant mission stations, the Catholics would need a vessel of their own, since commercial shipping was unreliable and could involve long delays. Hence, the vicariate set aside the funds for its own ocean-going ship and in 1907 an American captain was commissioned to draw up plans for the vessel. The following year he and Br. Karl Zimmer, assisted by some of the Marshallese students, began the construction of the ship. In May 1910, the project was completed and the ship was christened the Regina. It was a two-masted cutter of 25 tons, 51 feet long and with a cabin outfitted with four bunks as well as smaller quarters below for the five-man crew. A captain was found for the ship in Br. August M ller, and it soon began to sail between mission stations bringing supplies, mail and sometimes personnel.  Church in Likiep in 1910 The Germans had succeeded in establishing an admirable foundation for their work in the Marshalls. The three mission sites were outfitted with fine buildings, linked by a mission ship, and staffed at a level that has not been equalled since. Jaluit, the pride of the mission, was equipped with a classroom building and a two-story rectory and an even larger convent that would have done credit to any community in the Pacific. By 1913, when its enrollment reached 80, the Jaluit school had attained such a pinnacle of esteem that commoners were braving the fury of their own pastors and enrolling their children in the school. In fact, the school added a number of day students to its growing number of boarders and the student body was split into four sections, two of them for full-blooded Marshallese. Yet, after ten years of labor, overall progress in the mission remained slow. The enrollments of the other two schools, which often plunged unexpectedly, never rose as high as the missionaries expected; in 1911, Likiep only counted 40 students and Arno 25. There had been some  Sisters in the Marshalls Mission, 1910 "conversions in ten years, but the Catholic population of the Marshalls in 1911 stood at only 180, less than half the number of Catholics in Nauru alone. The founder of the Congregation of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, after a visit to the mission sites in 1911, was so discouraged with the results that he considered the possibility of pulling the sisters out of the mission and looking for a more promising field of work. When he wrote to Rome confessing his doubts, he was thanked for the heroic patience his sisters showed and urged to let the sisters remain in the Marshalls in the hope that they would obtain greater results in the future. In the meantime, Fr. Bruno Schinke, formerly the MSC mission superior, replaced Fr. August Erdland as vicar of the Marshalls in 1911. Fr. Erdland left the mission, together with two of the sisters who had to return to Germany because of poor health. Two others, Srs. Stanisla and Benedict, had died of tuberculosis in 1906 and 1907 respectively, one of whom was buried on Jaluit. Frs. Kiefer and Wendler also died at their posts in Likiep a decade apart, and two more including Fr. Schinke, the newly named vicar would die between 1916 and 1918. There were 20 missionaries still at work in the Marshalls in 1914 besides the two priests and four sisters assigned to Nauru. Likiep and Arno each had a priest and three sisters; the other 12 religious were stationed on Jaluit.  Church in Jaluit One day in late September 1914, the Germans were startled to see six Japanese warships steam into view off Jaluit and come to anchor. The ships disgorged hundreds of Japanese marines, who overran the small Germany colony with fixed bayonets. The school girls and sisters, thoroughly terrified, took refuge in the rectory for the rest of the day. Japanese officials visited the mission the next morning to announce that they had taken the islands from Germany, with whom they were at war, but they politely expressed an interest in the mission's work and promised that they would do nothing to interfere. A week later all the German government officials were expelled, but the missionaries were allowed to continue their work without restrictions for another year. Then, in September 1915, the Japanese authorities announced that the mission personnel would have to stop teaching the German language although they were permitted to teach other subjects in their own tongue. With the expulsion of most of the German nationals in business and government, the enrollment of the Jaluit schools had dropped sharply. Moreover, the political changes were making the German-run school, once the pride of the German Micronesia, increasingly irrelevant. The enrollment stood at only 24 when, toward the end of 1915, the Japanese issued a proclamation requiring all students to attend the government-run public schools. All private schools were to cease operations, even though children were permitted to continue living with the missionaries and could receive religious instruction and manual training. Soon the missionaries found themselves confined to their single main station on Jaluit. In September 1915 all the German priests and sisters on Nauru were taken off the island and interned in Australia for a few months prior to their repatriation. The station on Likiep was shut down in 1916 when the pastor was transferred to Jaluit to replace Fr. Schinke, who had just died. The Arno station was closed about the same time after the Japanese issued an order requiring that all Germans be brought to Jaluit. For the following three years, more than 20 missionaries operated out of their quarters on Jabwor, Jaluit, visiting other places only when they could secure the necessary permission to travel to other atolls. It was in June 1919 that the final blow fell; the missionaries were informed by Japanese military authorities that they must all leave the Marshalls. On June 22, a simple mass was said in the chapel, the sanctuary lamp was extinguished, and the German missionaries were led to the dock to board the Japanese minesweeper Hatsuriki that would bring them to Yokohama. The goodbyes with their small Marshallese flock were so emotion-filled, one of the sisters wrote, that many of the Japanese bystanders had their eyes fill up as they watched. Even as they departed, the German missionaries left a rich bequest to the people with whom they had worked for the past 20 years. There were over 200 baptized Catholics and another 40 people under instruction at the time of their departure. To help instruct and sustain the faith of these converts, the missionaries had also brought out numerous publications in Marshallese: bible readings, catechisms, bible histories, prayer books and song books. The years following the expulsion of the missionaries were trying ones for the Marshallese Catholics. They were a small minority in a society that was generally hostile to their religious beliefs, and they were taunted for their reliance on the foreign priests who had been forced to leave them. Yet, Catholics on Likiep, Arno and Jaluit still gathered every afternoon for rosary; the prayers were led by one of the people and were preceded and followed by a hymn. On Jaluit, Maria Milne, one of the former boarding students, served as a catechist to the Catholic population; she went around instructing people in prayers and basic beliefs and assisted the dying in their final hours. For years she faithfully wrote the sisters who had taught her, informing them of what was happening on Jaluit and always, at the end of her letter, begging them to return as soon as they could. Spanish Interlude As soon as the Japanese established legitimate title to the islands they had seized from Germany at the start of the war, they made known to the Vatican their desire to have Catholic missionaries work in the Mandated Territory. Their motives were much the same as the Germans 25 years before: missions were seen as a pacifying and civilizing influence on the islanders. Spanish Jesuits were brought in to take over the Catholic missionary work in the Carolines and Marianas in 1921, but the Marshalls was in a strange position. Although it was still officially a separate vicariate entrusted to the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, Japan was unwilling to have missionary personnel from Germany, its former enemy, resume work in the islands. The Marshalls was once again an unmanned jurisdiction, a vineyard without laborers, until, in early 1922, the Society of Jesus was asked to take responsibility for the island group. A year later, by a decree of 4 May 1923, the Marshall Islands was formally attached to the Vicariate of the Carolines and Marianas, with Nauru annexed to the Gilbert Islands.  The Early Jesuits in the Marshalls: 1920s From the outset, the Marshalls was the poor cousin of the Jesuit mission. The first Jesuit priests and brothers, who had landed in Micronesia in early 1921, all had assignments by the time the Marshalls was added to the mission. Fr. Santiago Lopez de Rego, the apostolic administrator of the vicariate, had to dig deep into his thin personnel to come up with four Jesuits to staff the two houses he proposed opening in the Marshalls. Fr. Jose Pajaro, an accomplished linguist who spoke six or seven languages, was transferred from Chuuk, where he had worked for a year, and Victoriano Tudanca was moved from Pohnpei. The two of them were assigned to reopen the old German mission on Jaluit; while two more recent arrivals, Fr. Ramon Suarez and Br. Francisco Hernandez, were to go to Arno. For lack of manpower, the old station on Likiep would not be reactivated.  Abandoned Mission School in Arno The four Jesuits reached Jaluit in early January 1922. There they found the mission heirlooms, a pretty little wooden church and two beautifully constructed residences, far better than anything they might have imagined. The buildings had suffered relatively slight damage in the three years since the German missionaries had left the Marshalls. The Jesuits could only wonder at the marvels that their German predecessors had worked: a magnificent physical plant on each of the three islands in which they had stations and a much-acclaimed school system staffed by fine teachers. Yet, the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, with all their resources, had a disconcertingly small return to show for their efforts. What could the Jesuits, with their even more limited resources, expect to do in an archipelago renowned for its tenacious Protestantism? "We are leaving the hundred to pursue the single stray," Fr. Pajaro wrote; "yet this field has so far failed to yield a return equal to even one percent of the effort put into it." While Fr. Pajaro and Br. Tudanca began anew in Jaluit, Fr. Suarez and Br. Hernandez sailed to Arno to reopen that station. Upon arriving at the mission compound in Ine, they found themselves sharing the premises with a pair of Japanese traders who had settled in some months before. The buildings on Arno were not as well preserved as those on Jaluit. The roofs had deteriorated over the years and there were so many leaks that during a sudden rainstorm there was only one small corner in which the Jesuits could keep dry. The church was in even worse condition. All but a section near the main altar was exposed to the elements, and the rain had rotted much of the interior, including the two side altars and all the books and altar cloths stored in the sacristy. A few days after the arrival of the Jesuits, a Marshallese man paid them a visit and promised that he would take care of fixing the church roof. Two weeks later, 50 women, probably the entire adult female population of Arno, appeared at the mission and spent the day weaving the thatch that their husbands later installed atop the church. A few days after the work was completed, on the Feast of St. Joseph, the church was blessed and the Blessed Sacrament was reserved in the tabernacle. "Now that the church is done," Suarez wrote, "it's too bad there are no people to fill it." The Jesuits found no more than a handful of Catholics 25 in Ine and another 17 in the village of Arno. The number who regularly attended Sunday mass was between ten and 15, and even on Easter there were no more than 20 in the church. On Majuro, which was also part of the parish, there were no Catholics at all, though German priests had visited the atoll on several different occasions. Hence, the Jesuits ministered to about 40 Catholics, most of them indifferent and casual church-goers, in a combined population of about 600 on the two atolls. The missionaries tended to blame the tepidity of their small flock on the social climate that surrounded them: the deeply entrenched Protestantism, their people's servility towards the chiefs, and the community pressure towards conformity. The initial show of camaraderie by the island people in roofing the church misled the missionaries into believing that the Protestants would prove receptive to Catholicism. Indeed, within their first few months on Arno, they had three proselytes under instruction. But very few others showed any interest in becoming Catholics, and the Jesuits had little to do but minister to the religious needs of their tiny community. The Catholics on Arno could scarcely even be called a community. They were, rather, scattered individuals whose fragile unity lay in the fact that they had ruptured their ties with the island's religious community. Protestants, on the other hand, had woven their church into the social fabric of Marshallese society; There were monthly collections, church committee meetings, festivals celebrated with dance and song, besides the daily ritual of religious activities. The conch shell was forever being blown, the Jesuits reported, to summon the villagers to bible study, hymn practice, prayer service or some other function.  Fr. Roman Suarez with visiting priest and parishioners The missionaries were treated with the customary Marshallese kindness and generosity. The evening before Suarez and Hernandez left for Jaluit to make their retreat, the village feted them with a late-night banquet, offered them food and cash gifts for their trip, and expressed the hope that they would be returning. Nonetheless, the Jesuits' work was going painfully slowly. Fr. Suarez had been on the island seven months before he was first called to administer the last sacraments, and then he found that the sick young man he was called to see had never been baptized. The priest gave the youth some medicine and promised to return the next day to perform the baptism, but the man suddenly recovered and made it known that he no longer wanted to be baptized. On visits to other atolls, the Jesuits spoke to whomever they met about their church and their faith, and even taught people the sign of the cross, but there were few dividends from such excursions. The missionaries on Arno were forced to conclude that nothing much could be accomplished with adults. If there was any hope for progress, it was through the children.  Fr. Jose Pajaro and some of his flock In Jaluit, Fr. Pajaro was coming to the same conclusion. In an attempt to build on the achievements of the German missionaries who preceded him, Pajaro gathered half a dozen young students and reopened the boarding school. Pajaro was the only Jesuit in the mission equipped to run a school, since his fluency in Japanese permitted him to comply with the government regulation that all instruction be given in the Japanese language. His knowledge of English was an additional inducement for parents to send their children to his school. Even so, his school was never as well attended as the old German school. He had no more than 14 students during the early years, although the enrollment gradually built up to 20 or 30 by the end of his ministry in 1934. Work limped along in the Marshalls for two years as the Jesuits filed one report after another of the frustrations they met in this difficult field. Pajaro and Tudanca were sent to Likiep in June 1923 to see whether prospects for a mission there were any better than on Jaluit. Accompanied by two of their pupils, they worked among the largely half-caste population of that island for the remainder of the year. Then Fr. Pajaro became ill and had to be moved out of the Marshalls to convalesce. About the same time, Fr. Suarez, whose two years on Arno were an exercise in futility and who did not even have a school into which he could channel his energies, also left to take a new assignment. Bishop Rego (he had been raised to the  Fr. Jose Pajaro, SJ "episcopacy in 1923) desperately needed men for the growing Catholic population on Chuuk and Pohnpei. How could the Jesuits justify continuing their unproductive stations in the Marshalls when other parts of the mission were clamoring for priests? Suarez and Pajaro were transferred to Pohnpei for a year and later to Chuuk to assist the expanding Catholic communities there. In 1926, after a two-year absence, the Jesuits decided to make another attempt in the Marshalls. Fr. Antonio Guasch, who had just served in Japan for six years as mission procurator and university professor, was assigned to Jaluit with Br. Pedro Espuny. The idea of reopening the Arno station was not even considered, so unsuccessful had it been a few years earlier. Guasch's year and a half in Jaluit seem to have been uneventful but for the fact that the first Marshallese was sent off to the seminary in 1926. Ferdinand Smith joined eight other young men from the Carolines and Marianas on a trip to Tokyo, and thence to Manila, to begin studies for the priesthood. He and all his companions except Paulino Cantero eventually left, and at his return from the seminary Ferdinand went on to work with the priests in the Gilberts for a time. Fr. Pajaro, by then seemingly restored to health, returned to the Marshalls with Fr. Fernando Hernandez in 1928 to replace Fr. Guasch and Br. Espuny. Pajaro resumed work in his Jaluit school, which had not suffered too greatly in his absence. The enrollment continued to rise slowly and, even more important, so did the baptisms of students and their parents. During the early 1930s he had an average of ten baptisms a year, and in 1933 and 1934 the yearly totals were over 20. By past standards in the Marshalls, these were very successful years for the Catholic Church on Jaluit. Elsewhere, however, the story was the same as in the past; the missionaries had very little to show for their efforts. On an island he was visiting in the course of a field trip in 1930, Pajaro was invited to say mass in a hut. Two days in a row, no one showed up either for mass or the talk the priest had been asked to give the entire community, Catholics and Protestants, afterwards. Pajaro was astonished at this, since all day long people had been idling around the hut eager to see their new visitor. On the third day, as he was vesting for mass, the Jesuit discovered the explanation: a man on a bicycle was pedaling around the clearing ringing a bell and furiously waving people away from the temporary chapel. Marshallese resistance to the Catholics remained as strong as ever in most communities. When the high chief of another atoll visited Pajaro by surprise one evening, it was only to borrow the stereoscope with which the priest had been entertaining some children the day before. Pajaro's attempt to convince the aging chief to become a Catholic before he died met with nothing but respectful if slightly embarrassed silence. In early 1934, Pajaro became ill again, and when he took a turn for the worse in June, his superiors made plans to evacuate him to Pohnpei. Upon the advice of a Japanese doctor, the priest was put aboard the Kasuga Maru with Br. Hernandez to nurse him. For the first two days of the voyage, Pajaro seemed to improve somewhat, but on the following morning, just as they were passing the island of Kosrae, the priest died. His body was carried to Pohnpei where it was interred in the mission cemetery in Kolonia. Pajaro's death meant the end of a permanent residence in the Marshalls, even though Jesuits from Pohnpei made yearly pastoral visits for the next few years. Fr. Higinio Berganza, the Jesuit mission superior, paid a brief visit to Jaluit in June 1935 to provide such pastoral care as he could in the three days he was there. Using as interpreters a Marshallese woman who had lived some years in the Philippines and an elderly Mexican lady, Berganza baptized seven children, officiated at two marriages, and provided some basic instruction for the Catholics who happened to be on island at the time. Each of the following three years, Fr. Berganza spent about a month in the Marshalls between ships. There was no time to visit any of the other islands, but the priest conducted daily catechism class for children on Jaluit and baptized several of his pupils each year. As the priest went about his work, Br. Hernandez made repairs on the roof of the church and the other mission buildings. When Berganza left the mission for Japan in 1939, Fr. Gregorio Fernandez replaced him on these excursions. Like Berganza, he concentrated on work with the young; he taught children how to make the sign of the cross, how to say the Our Father and Hail Mary, and the rudiments of the faith. A number of baptisms were recorded during his visits in 1939 and 1940. Fr. Gregorio was so well liked that the Catholics of Jaluit sent a written petition to the ecclesiastical superiors asking that he be permanently assigned to the Marshalls. With the clouds of war gathering in 1940, Japanese authorities forbade such visits from that time on. Spanish Jesuit activity in the Marshalls, even on such an occasional basis, ended in that year. Spanish Jesuits, unused to the demands of apostolic work in a religiously pluralistic society, were probably not the missionaries best suited to staff the Marshalls. Yet, they did it just the same by starts and fits, to be sure but at considerable cost to the individuals involved and to the rest of the mission. Despite the sluggish pace of progress, especially in the beginning, they registered a church enrollment of over 500 by 1940, thus doubling the size of the Catholic community in 20 years. American Restoration The war brought its share of personal tragedy to all Marshallese, irrespective of their church affiliation. Carl Heine, the foreign-born trader who sank roots in the islands and became its foremost Protestant missionary, was executed by the Japanese in the early 1940s. Also executed were two Sacred heart priests, Frs. Durand and Marquis, who set out from the Gilberts and were lost at sea for three weeks before washing up on Mili in September 1943. The priests, who were arrested and interrogated by the Japanese military police, suddenly vanished from sight until their bullet-ridden bodies were found offshore and secretly buried by some Gilbertese Catholics. Some Marshallese survived only by virtue of extraordinary fortitude and resourcefulness, like the young church leader on Likiep who, upon learning that he was marked for execution, swam across the lagoon towing his mother on a wooden plank and completed his escape to another atoll on a small boat.  Fr. Feeney with Maryknoll sisters at the Likiep dock The war also brought devastation to those splendid mission stations that were built by the German missionaries in the first decade or two of the century and had served the Spanish Jesuits so well in more recent years. The Likiep church was used as a copra warehouse and the Japanese converted the church on Jaluit into a radio station. None of the mission stations suffered more than Jaluit, which was hit repeatedly by incendiary bombs in the later years of the war. An American priest visiting Jaluit shortly after the war described the remains: the floor ribs of a 60-foot long skeleton church, the rubble of the two-story convent and girls school, the wreck of the boys school and rectory. In the debris he found a sanctuary lamp, its chrome holder unstained, a dozen figurines from a Christmas crib, and a large statue of St. Joseph that had been beheaded. Jabwor Island, the capital of the Marshalls for 60 years under two colonial governments, was deserted; the islet, once the center of Catholic missionary activity, was now a wasteland and the Catholic population dispersed. Soon after the mission was turned over to American Jesuits, the newly named apostolic administrator, Fr. Vincent Kennally, made a short visit to Eniwetok and Kwajalein in early 1946. The next year he was back again for a much longer stay. For two months, between February and April 1947, he surveyed the condition of the church in the Marshalls, visiting nine atolls. He found that despite the devastation of the old Jaluit station, the mission buildings on Likiep were in surprisingly good shape. Many of the old mission school graduates from Jaluit were now settled on Likiep, which had over 100 Catholics, most of whom showed up for mass on his first morning there. There were another 40 Catholics on Ailinglapalap, where Kennally baptized an additional ten people; there were also a smattering of Catholics on Ebon and Namorik.  The mission vessel Regina II What should be done with the Marshalls? Desperately short of mission personnel but faced with the problem of staffing a huge stretch of the western Pacific, Kennally wrestled with the old question once again. He flew to Tarawa to inquire whether the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, who were still manning the Gilberts, could possibly take over the work in the Marshalls. This was out of the question, he was told; the 16 priests still laboring there were all too old for such an undertaking. Later, after consultation with two of his Jesuit advisors, he wrote to the Superior General of the Jesuits recommending that the Marshalls be surrendered to another religious order. Fr. General approved, but no other order could be found to accept this mission. So, the American Jesuits, like the Spanish Jesuits 25 years earlier, made a hesitant commitment to staff the Marshalls. The first two American Jesuits, Fr. Thomas Feeney and Fr. Thomas Donohoe, appeared in October 1947. The pair was a study in contrast: Fr. Feeney, the urbane Bostonian who had written several books and would soon publish another on the Marshalls, and Fr. Donohoe, the plain-spoken and rambling midwesterner who preferred the remoter islands. The two priests were immediately assigned to Likiep, which was chosen as the main mission station in the Marshalls. The Jesuits briefly considered establishing their base on Majuro, the headquarters of one of the two naval commands and the site of the new teachers training school. Although the Catholic population of Majuro was only about 50, this atoll seemed likely to eventually become the center of commerce and government. But Likiep offered several uncontestable advantages at that early date: besides its relatively large number of Catholics and the undamaged state of its old mission buildings, Likiep was close to Kwajalein, the main American base and the hub of air transportation in and out of the Marshalls. On Likiep the priests found a solid group of co-workers: Alphonse Capelle, the spokesman of the Catholic community; Maggie Capelle, for years the island sacristan and catechism teacher for the children; and Cecilia DeBrum, who was then and in future years one of the most tireless supporters of the church. There was a great deal to be done, for no priest had been to Likiep for 14 years. Only three of the young Catholics on the island had ever gone to confession and none had yet made their first communion. The priests began holding religious instruction classes three evenings a week and had the old prayer-hymn book, Jar im Al, reprinted. They also began making improvements in the mission facilities. To the German-built rectory in which they lived, they added two storerooms, a large porch on either side, and a few sheds. Once they hooked up the generators they brought with them, Likiep experienced for the first time the marvels of electric lights and ice cubes. Even as they went about their work on Likiep, the two Jesuits began taking turns making visits to other atolls, using navy LSTs, copra ships or whatever transportation they could find. Once they were forced to charter their own vessel, a locally owned trade boat, that nearly sank beneath them. Usually, of course, the priests were at the mercy of the ship's schedule, which often left little time for even the essential pastoral ministry in those rarely visited islands. In March 1948, Fr. Feeney obtained a salvaged navy launch that he hoped to use as a regular mission vessel. The 50-foot ship was fitted with sail by Likiep carpenters and christened Regina II, a worthy successor to the German mission vessel. On this ship the Jesuits began making their pastoral visits to other atolls.  Lessons in carpentry at Likiep school  Holy Rosary School in Likiep "Within a few months, the Jesuits opened a school of sorts, with 65 pupils of all ages loosely divided into classes. One of the priests taught religion and English, while Almira DeBrum and Ellen Capelle instructed the school body, who ranged from five year olds to youth in their early twenties, in all other subjects. Holy Rosary School, as it was called, could not quite decide what it wanted to be, so it offered something of everything. If ever there was a community school, this was it. Under the tutelage of Fr. Feeney, the children ran a bookstore cooperative which proved so successful that its stock was expanded to include food and later building supplies and membership was offered to adults. With the early missionary emphasis on economic self-reliance and vocational training, the school soon taught a melange of trade skills. Fr. John McCarthy, who arrived in late 1949, set up courses in photography and engine mechanics for a while, and then introduced the older boys to carpentry and navigation. Later he started them on Morse code and radio electronics, and next moved into bookkeeping and finance. Holy Rosary School badly needed the organizational hand that the Maryknoll sisters brought it when the first three began teaching on Likiep in September 1950. Housed in a new two-story convent, Sr. Emily McIver, Sr. Rose Patrick St. Aubin and Sr. Camilla Kennedy began shaping Holy Rosary along more conventional elementary school lines. Side by side with Ellen Capelle, Cecilia DeBrum and Almira DeBrum, the sisters taught in a long building without interior walls; only makeshift partitions screened the classes from one another. The year after the school opened a full elementary program, students began attending from other atolls and its enrollment rose to nearly 100. Soon the sisters added a dormitory for girls with supervised study by electric light in the evenings. The school was an immediate success: some of its graduates went as far as Hawaii for further studies in a day when few had the opportunity to travel beyond Micronesia, and three girls, including Ann DeBrum from Likiep, entered the Mercedarian convent on Saipan. At the arrival of Sr. Rose Leon Andrews in 1953, the Maryknoll Sisters extended their apostolate beyond education, for Sr. Rose Leon, a trained nurse, opened a dispensary to provide medical care for the community. Their work bore immediate fruit: throughout the 1950s, an average of six or seven non-Catholics were received into the church each year. In the summer of 1949, just a few months before Fr. McCarthy's coming, Fr. Tom Donohoe moved to Jaluit to establish a second mission station there. He set up temporary quarters on Imroj, the small island to which many Catholics fled during the war, while his people cleared the old mission site on Jabwor for future rebuilding. In September he opened a small school for 26 children. With Maria Louis and Martha Makaphie, a graduate of the German school on Jaluit, he shared the teaching load in the four classes until the student body doubled two years later. Donohoe's right-hand man was Jimen Stephan, a former municipal policeman with a wealth of practical skills. It was he who supervised the cleanup on Jabwor, served as foreman for the construction work, maintained the boats, and took over the day-to-day management of the mission when the pastor was away.  Church on Likiep Although Fr. Donohoe met some initial resistance from the American Protestant teachers based in Kosrae, his relations with local Protestant leaders was relatively untroubled. "We don't have to be here long," he wrote, "to realize that our battle is not against Protestants, but against the principalities and powers...against the devil and all his works and pomps." Like the other American missionaries of his day, Fr. Donohoe saw economic development as an integral part of the church's work in combating all that dehumanizes; and like his colleagues on Likiep, he founded a cooperative store at which food and other necessities were sold at minimal cost. To permit him to travel as widely as he wished, Fr. Donohoe acquired two boats, a 25-foot vessel for travel in the lagoon and a 50-foot hull that he hoped to use for visits to other atolls. The latter was rebuilt by Kelen, a master boat builder, refitted for sail and engine, and renamed the St. Joseph. It was launched in October 1953. Meanwhile, the priest and his people continued the wearisome labor of readying the old mission site on Jabwor for habitation. They built a small residence there in 1950 and mounted in a prominent place the repaired statue of St. Joseph that they had salvaged from the ruins. Both were intended as pledges of what was to come not only was the former mission to be rebuilt, but there was to be a central boarding school large enough to educate 300 students, a trade school that would cast its shadow over the whole southern Marshalls area. Fr. Donohoe hoped to duplicate the construction feat of the German missionaries, but on a larger scale and in concrete rather than wood. Br. Michael Murray, who first came to Likiep in late 1950, was sent to Jaluit to assist Fr. Donohoe two years later. Fr. Feeney, named bishop-elect of the vicariate, left the Marshalls in 1951 to return to the US for his episcopal ordination and thereafter to take up residence in Chuuk. During his four years on Likiep, Feeney found time to edit for future missionaries a Marshallese dictionary that the Maryknoll Sisters had compiled from the notes of Freddie Capelle and publish his Letters for Likiep. Fr. John McCarthy, reassigned to Palau in 1953, was replaced on Likiep by Fr. Thomas Holland, who remained there for only two years before he too was reassigned to another part of the mission. Holland was replaced by Fr. William Farrell, who worked on Likiep for a year before he too was transferred elsewhere. In December 1952, the Marshalls received another priest who would play a leading role in the growth of the church over the subsequent four decades: Fr. Leonard Hacker. The Harvest Season  The Jaluit team: Fr. Tom Donohoe and Jimen Stephan Fr. Hacker was transferred from the Philippines to the Marshalls to found a Catholic mission on Majuro, an atoll that was fast becoming the political and commercial center of the archipelago. At that time there were only a few dozen Catholics on the island, and there was no church or meeting place. With the help of Dorothy Kabua, one of his first converts, Fr. Hacker acquired a piece of land and from discarded materials built a combination church and rectory that was blessed in September 1954. In keeping with the conventional wisdom of missionary work, the priest used work with the young as a means of gaining a footing in the society; he began holding catechism classes for children, something that soon evolved into a formal elementary school program. Assumption School opened in 1954 with not more than 20 students, mostly boys, and classes held in the mission chapel. Three years later the school enrollment was up to 100 and still rising. The ceremonies at the close of the 1957 school year lasted nine hours and featured a meal prepared and served by the cooking class.  Fr. Len Hacker and his renowned band In a few short years the Catholic community on Majuro had grown prodigiously. Not only was the school expanding each year, but the number of Catholics, at 120, was now double what it had been in 1952. But there were other projects besides: the chicken farm that was intended to help support the mission, and the boys band that played at nearly every island event. Fr. Hacker had to teach himself to read music and compose simple pieces before he could begin training his youngsters to play instruments that were sometimes as big as themselves. Br. Mike Murray came to Majuro in 1956 to help out for a few years, but local people provided most of the support for the growing mission. Ferdinand Smith, who as a young man had spent a few years in the seminary, worked with Fr. Hacker from the outset, instructing children in catechism, teaching in the school and working wherever he was needed. Cecilia DeBrum, who had moved to Majuro from Likiep, was one of the first school teachers; she worked with Elizabeth Marie Luz, a graduate of Likiep school. Assumption School had begun drawing so many students from other islands that a dormitory was fashioned from a navy surplus quonset hut. While Br. Murray taught class and tended the dormitory, supervising the 40 boys before and after school hours, Fr. Hacker began construction of the familiar two-story concrete building that would become Assumption School's main classroom building and convent. As the school gained the respect of the overwhelmingly Protestant community, it became more and more the central focus of the parish. When the enrollment outgrew the tiny teaching staff and school administration began to absorb nearly all Fr. Hacker's time, he turned to the Maryknoll Sisters for help. In February 1959, Sr. Mary Camilla, who had helped open the Maryknoll school on Likiep, was assigned to Majuro with two companions, Sr. Margaret Tryon and Sr. Rose Patrick St. Aubin, both of whom gave many years of service to the church of the Marshalls. Assumption School, with its school children dressed in uniforms of blue and white, was now in the hands of professional teachers. Its 200 pupils were packed into temporary buildings until the new concrete shell could be converted into classrooms.  The old dormitory at Assumption School In the meantime, the Jaluit mission, which was finally transferred from Imroj to Jabwor, went into a rapid decline. The opposition of Protestant pastors intensified and the school drew no more than 35 students, half the number enrolled on Imroj prior to its closing. As construction of the new church and school crept along due to lack of funds, the Protestants threatened to counter the Catholic move by opening a large mission school of their own headed by an American teacher. The situation had the makings of a head-on religious confrontation. Then, in January 1958, Typhoon Ophelia salvaged Jaluit even worse than the 1905 storm had. The people on Jabwor moved from one building to another to seek shelter, leaving each just as it was ready to topple. Fr. Donohoe watched as the mission possessions were carried off by the flood that engulfed the island; first the piano floated by, then the refrigerator, and finally a six-foot statue of Our Lady, still crated. The statue was later found in 60 feet of water, retrieved and displayed on the battered mission premises; but the mission boat St. Joseph, which slipped its moorings during the storm, was a total wreck. 31 people were killed and the property damage on Jaluit was almost total. Also demolished by the storm was any lingering dream of recapturing the island's past glory. The Catholics of Jaluit struggled to rebuild the mission, and Fr. Donohoe even constructed churches on two other atolls, Namorik and Ailinglapalap, but the mission hovered on the edge of extinction. There were as many Jaluit children attending the Catholic school on Majuro as on their own island. The parish had sent one of its girls, Dorothy Nook, to the Mercedarian novitiate, but even she was first sent off to Likiep to complete her schooling under the sisters. The Jaluit school limped along for several more years before it was finally closed in 1967. Bishop Kennally, who had succeeded Bishop Feeney in 1957, suggested that, in view of the devastation by the typhoon and the population shift to Majuro and Kwajalein, the Jaluit station be closed and Fr. Donohoe transferred to another island, but the priest was not prepared to surrender his beloved parish. He continued to work on Jaluit, but shifting his base of operations to Majuro, where he spent an increasing amount of his time. Likiep, too, was feeling the impact of the population movement towards Kwajalein and Majuro. Fr. John McCarthy returned from Palau as pastor of Likiep in 1956 to find his small congregation drifting off to other places. Maryknoll sisters continued to be assigned to Holy Rosary School, even though the student body was diminishing year by year. In 1962 alone, the school lost 30 of its pupils to Majuro, Fr. McCarthy reported. The Jesuits wondered whether it was worth maintaining a station there, but it was not easy to close a station that for ten years had the distinction of being the center of Catholic work in the Marshalls. With the continuing decline in enrollment, however, the school on Likiep was finally closed in 1964. In the meantime, Likiep became a base from which to launch excursions to other atolls. A new church was built on Eniwetok in 1956, and plans were developing to begin work on Ebeye. Before his death, Bishop Feeney had acquired title to some land on Ebeye and gathered materials with an eye to building a small church. Local opposition against the Catholic presence was strong, however, and the Jesuits soon found themselves embroiled in another major controversy. When some of the Ebeye people threatened to raze the church, the Jesuits got a court injunction to restrain them from doing so. Construction of the new church resumed, but was stopped again in the summer of 1956 as the public outcry against the church grew stronger. While this dispute was going on, the mission ship Regina was lost when it went on a reef one night and was pounded to pieces before it could be salvaged. Fr. McCarthy found a replacement, a navy seaplane refueling launch, but the new vessel, called the Bobola, was in need of major repairs and was not ready for operation until 1962. By that time, the chapel on Ebeye was built and a foothold secured on that island. Afterwards, Fr. McCarthy divided his time between Likiep and Ebeye, later moving to Ebeye where many of his former parishioners had gone. The 1960s were transitional times for the church in the Marshalls. It was an especially difficult period for the Catholic communities and their pastors on Likiep and Jaluit, as the latter watched the accomplishments of the previous decade slip away. Many of the best graduates of their schools, along with some of their older church leaders, joined the numbers of Marshallese streaming into the new port towns to find jobs or continue their schooling. The Catholic schools on both islands were closed in the mid-1960s, and the resident pastors began looking for other activities to absorb their time and energy. Transportation to the other outer islands was a more critical need than ever, now that pastors were more free to visit other places. In 1962 an American couple, Jack and Dorothy Binns, put themselves and their 38-foot schooner Capella at the disposal of the church in the Marshalls. For two years they carried mission personnel and their students up and down the island chain, providing special assistance to Fr. Donohoe, until the schooner struck a reef one evening in May 1964. The vessel was a total loss and the mission could not afford a replacement; the age of mission-owned ships was over. On Majuro, in the meantime, the church was enjoying a period of rapid expansion. Fr. Hacker was forced to add a new wing to Assumption School in 1963 to keep up with the rapidly growing enrollment. Even before this was completed, work was begun on another of the auxiliary buildings that were soon sprouting up all over the mission property. There was scarcely a month during the 1960s and 1970s when cement was not being poured or boards sawn for some new structure; and boys and women worked each afternoon carrying sand and gravel for the construction. Maryknoll Sisters' replacements for the teaching staff included Sr. Joan Crevcoure and Sr. Rose Lauren Earl, both of whom served as principal of Assumption for several years. Fr. Frank Staebell, a longtime presence in the Marshalls, arrived in 1965 to teach in the school and help in the parish. There was also a growing cadre of Marshallese teachers in the school, among them Veronica Balos, Mary Libiel, Boj Nepthali and Morris Jetnil, who faithfully served the parish school for years afterwards.  Maryknoll Sisters outside their new convent in 1966 In addition to the school, which by the late 1960s had about 300 students, the parish ran a number of other programs: the band, cooking classes, a handicraft club, adult religion instruction, and various women's programs. Fr. Hacker, the tireless pastor, even operated his own bus service on Sunday mornings, picking up Catholics for mass and dropping them off at their homes afterwards. Amid this whirlwind of activity, he and some of his talented parishioners Dorothy Kabua, Herman Schmidt, Daisy Capelle and Maggie Capelle also found time to compose liturgical songs and publish books of Marshallese hymns. He also collaborated with the Congregational church on a new translation of scripture into the local language, a telling sign of how far ecumenism had advanced since the war. On Ebeye, which had a resident priest only after the Likiep school closed in 1964, progress was much slower. The small wooden church that brought on such a storm of controversy remained unfinished until 1967 when the steeple was finally added. Even then, however, there was no rectory. When Fr. McCarthy left the Marshalls in 1966, other priests had to cover Ebeye as best they could for nearly a year until Fr. Frank Staebell was transferred from Majuro to Ebeye in late 1967 to become its full-time pastor. Aided by Angelina Capelle and others from her family who had moved from Likiep, Fr. Staebell ran catechetical programs for the young and provided spiritual assistance to the growing Catholic community on the island. For 11 years, a difficult period of social turmoil for the crowded island population, Fr. Staebell served as pastor. Although Ebeye still did not have a Catholic school of its own, a number of its young people, as well as those from other islands, were sent to Majuro to attend Assumption School. Br. Jerry Schade came to Majuro in 1968 to run the dormitory and teach in the school, as Br. Mike Murray had ten years earlier. Many of the more gifted Assumption School graduates were going on to Xavier High School in Chuuk afterwards. From their number would come some of the most prominent government and business leaders in the Marshalls, not to mention a few of the men who played major roles in the church of the 1970s and 1980s. Girls of exceptional ability were generally sent to Mt. Carmel on Saipan or one of the academies on Guam. For some years the parish had given some thought to expanding Assumption School from eight grades to 12; in 1972 a ninth grade was finally added, Sr. Emily McIver appointed principal, and the first high school graduation held four years later. Catholics of the Marshalls now had their own high school, which would soon be distinct from the elementary school although governed jointly by a single school board. A new generation of mission school graduates were now making an appreciable contribution to the church on Majuro. Elenjen Tibon, a Xavier graduate with limitless enthusiasm, organized youth groups, set up sports leagues and produced radio programs, when he was not in the classroom teaching. He later became the first Marshallese principal of Assumption School. Mary James, one of the first graduates of the elementary school in 1961, has been teaching at that school since her return from college in 1973. Marie Maddison brought a quiet confidence and competence to the school, as did Biram Stege in more recent years. Joe Jie served as a lay apostle to the outer island churches, and several of the present Assumption School staff, including Sandy Dismas, the elementary school principal, are products of the mission schools.  Assumption School, Majuro There were several personnel changes among the missionaries during the 1970s. Fr. Frank Zewen, a diocesan priest, spent some years on Majuro assisting in the parish as he completed his linguistic studies. For a time, during the absence of Fr. Donohoe, Fr. Dave Young provided service for the outer islands, and Fr. Tom McGrath worked on Likiep for a year between assignments on Guam. The flow of Maryknoll sisters continued Srs. Lucille Witkewiz, Ester Donovan and Norbert McLaughlin all arrived during these years but the role of the sisters was changing. No longer were they simply school teachers, as they had been for so long. In 1968 Srs. Joan and Rose Patrick began their long and dedicated ministry to the outer islands, and by the late 1970s a pair of sisters were on Ebeye doing parish and community development work. Although the initial emphasis in the outer islands was on pastoral work, the sisters and Fr. Dave Young soon opened small Catholic schools on Jaluit, Arno and Wotje, a significant start to reversing the trend of the previous 20 years. During the years when no priest was available in the outer islands, Frs. Joan and Rose Patrick intensified their efforts to develop effective prayer leaders in each community. They trained the prayer leaders to baptize infants and to conduct communion services, reestablished churches on Ailinglapalap and other places, revised the prayer and hymn book, and encouraged their Catholics to seek new ways to pray together. Fr. Jim Gould, who arrived in 1983 to assume care of the outer islands when Fr. Donohoe finally retired, worked with the sisters to further these directions. He has gathered the outer island prayer leaders for a two-week workshop each summer since then to prepare these men to play a greater role in the church life of their priestless communities. He and the sisters on the pastoral team have continually made the rounds of the outer islands, overseeing the progress of the schools and caring for the spiritual needs of people who would otherwise have been forgotten. In May 1977, the Catholics on Majuro celebrated the dedication of their new and artfully designed church, one that had been several years in the building. Soon afterwards, Fr. Hacker, who had been pastor of Majuro 25 years, was sent to Ebeye to replace Fr. Staebell. Barely had Fr. Hacker settled on Ebeye when he was building up rather than out due to the space limitations on the small mission plot. In a few years, Queen of Peace Elementary School opened, expanding classroom by classroom until it had a student body of well over 300. Sr. Emily McIver and Sr. Miriam de Lourdes pioneered in the school together with a Marshallese staff; later a convent was built and Notre Dame religious were invited to work at the school to replace the Maryknoll Sisters. During the late 1980s, a Yapese nun, Sr. Walter Marie, was principal of Queen of Peace. Still building despite his serious eye problems, Fr. Hacker erected an ornate cement church that was dedicated in 1987. The size of the Catholic community on Ebeye remains fairly small, but the educational contribution of the church there has been enormous. On Majuro, meanwhile, a new thrust in church work began in the late 1970s with the assignment of Fr. Tom Marciniak to the Marshalls. For the three years before he succeeded Fr. Staebell as pastor, his task was to prepare to do leadership training programs for Marshallese laypeople. With Fr. Jim Gould, he began the yearly summer workshop for Catholic prayer  Fr. Frank Staebell, Fr. Len Hacker and Br. Jerry Schade "leaders, and initiated a deacon training program for the Marshalls. The three candidates Alfred Capelle, Tony Mamis, and Thomas Makiphie were ordained to the diaconate in February 1986. After their ordination, besides fulfilling their liturgical roles, they assumed various responsibilities for the parish and the schools. Fr. Marciniak also tried hard to add new zest to the parish liturgy through the careful training of ministers and addition of tasteful music to the celebrations. Lay involvement in the life of the parish has also increased during this past decade, with parish groups becoming more active than they had been in past years. One of the most vigorous, the women's club, has taken a leading role in sponsoring days of prayer, seminars and social events. Partly as a result of its activities, several of its members gained the confidence and experience to serve as catechists for the parish. The size of the Catholic population in the Marshalls, now estimated at about 4,000, has grown substantially since World War II and parish demands have multiplied accordingly. Even so, the church's main effort in the Marshalls is, as it has always been, educational. Never before, even in those golden years of the German missionaries, has the church's educational apostolate flourished as it does today. The five Catholic elementary schools have a total enrollment of over 1,000, with much of the leadership in recent years coming from Marshallese. Assumption High School has had its share of problems, including a sharp drop-off in enrollment, but the capable guidance of Sr. Aurora de la Cruz and Sr. Alice Juana has steadied the school. During the early 1990s a second high school was opened, this one a vocational school on Ebeye. Marcella Jonathan, a Marshallese lay woman, served as principal during its infancy, bringing it to stability. Besides running its own private schools, the church has also begun assisting public education. For a few years in the late 1980s Sr. Irene Nieland worked in the general area of health education; afterwards she and two other Franciscan sisters taught at the College of Micronesia nursing school. Another, Sr. Donna Williams, held an administrative position at the college. Although well established in the Marshalls today, the Catholic Church is far from being a truly Marshallese church. After years of struggle it has won respect from the society to which it was brought by the missionaries, but it has not yielded local vocations to the priesthood and religious life. A few young men from the Marshalls have entered the seminary since the late 1960s when St. Ignatius House opened on Guam, but only one of them remains and he has recently entered the Jesuit novitiate in California. Few young women have entered the convent despite the energetic example of Sr. Dorothy, who did outstanding educational work in the Marshalls in the early 1980s, and she remains the only Marshallese sister today. It was largely to encourage local vocations that Gilbertese sisters from the Congregation of the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, an offshoot of the congregation that staffed the mission during German times, were invited to the Marshalls. Since their arrival in 1989, these Sisters have been a dynamic presence, some of them teaching in the Majuro schools while others work with girls who express an interest in religious life. In the meantime, Pacific Islander priests and brothers from the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart have taken full responsibility for ministry on Ebeye. The Catholic Church in the Marshall Islands was given found recognition when, on August 15, 1993, it was split from the Diocese of the Caroline Islands and constituted a Prefecture Apostolic of its own. A year later, Monsignor Jim Gould was made the Prefect Apostolic of a church that is on the way to becoming a full diocese someday. That the church in the Marshalls is no longer the "unyielding field" of which earlier missionaries lamented is a tribute to the effectiveness of their work. The Catholic Church has grown in size and esteem to become an accepted feature of Marshallese life, respected for its contribution to the young nation. The first season of its growth is concluded, yielding a rich harvest. Ahead still lies the second stage in which it must develop local leadership if it is to become an authentically Marshallese church.

Hezel, Francis X. "The Catholic Church in Micronesia: Historical essays on the Catholic Church in the Caroline-Marshall Islands". ©2003, Micronesian Seminar. All Rights Reserverd. |